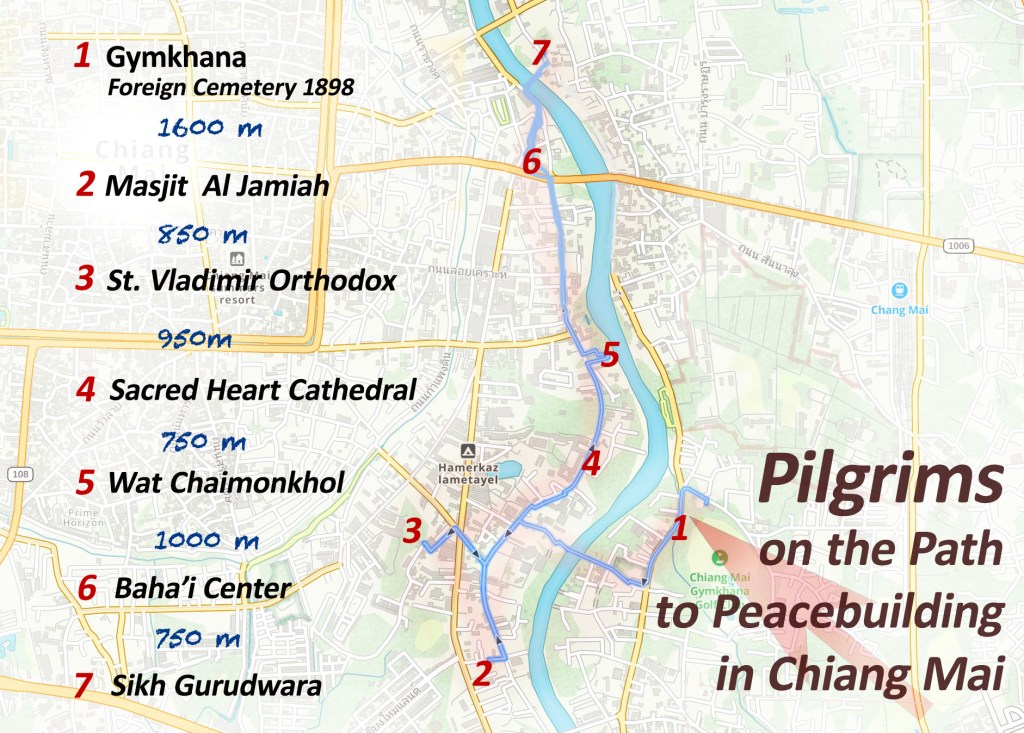

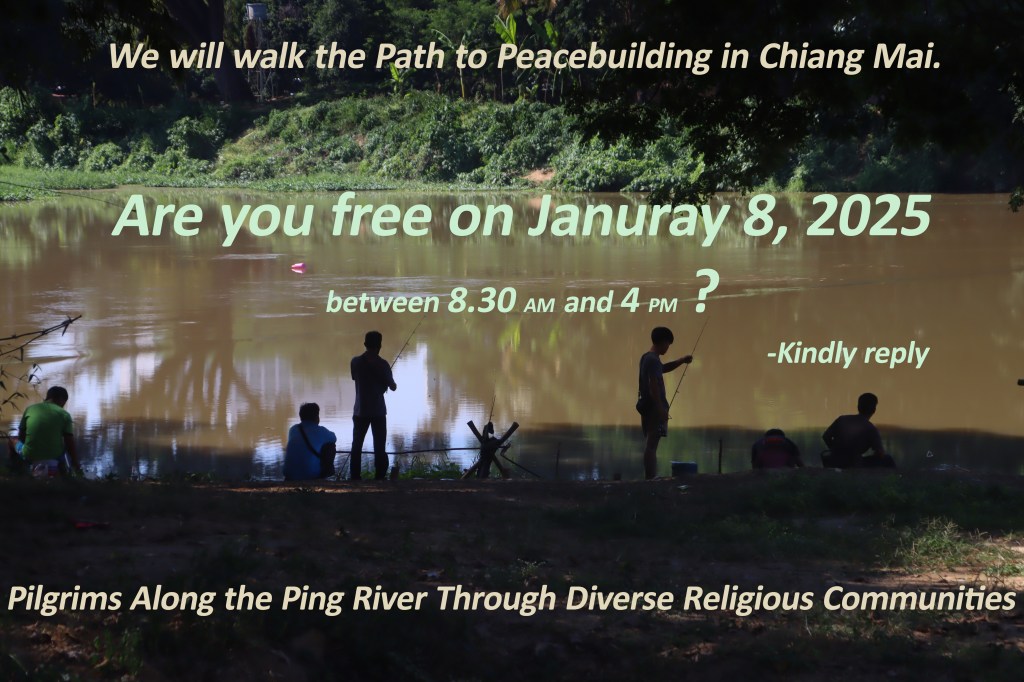

On the morning of January 8, 2025, the air is crisp in Chiang Mai. We gather in front of the Gymkhana Club. One by one, the participants arrive—former students, teachers, and members of local communities—all ready to embark on this unique walk. The idea is simple: to connect different places of worship on foot, creating a symbolic link between these spaces and fostering interfaith dialogue.

Why Organize an Interfaith Walk?

Cultural or religious visits are often static: we arrive at a place, listen to a presentation, and then leave. But what about the surrounding neighborhoods? What paths connect these spaces? Walking allows us to physically experience these connections and better understand how neighboring communities coexist.

I co-organized this event with the Payap Faculty of Peacebuilding.

Why This Neighborhood Along the Ping River?

In the past, Chiang Mai’s citadel was reserved for the royal family, clergy, and military. Ordinary people lived outside the moat, with each neighborhood home to a distinct community. When the first foreigners arrived, they were granted permission to settle along the Ping River, creating a cosmopolitan enclave of Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, and Buddhists—merchants from India, China, and beyond.

Why meeting at the Gymkhana Club?

Founded in 1898 by the British community, the Gymkhana Club tells the story of one of Chiang Mai’s first foreign communities. As a place that is religiously neutral yet deeply rooted in a spirit of sportsmanship, it seemed like the perfect starting point for our journey.

Why Start at the Foreign Cemetery?

In Asia, honoring ancestors and founders is an important tradition. The Foreign Cemetery was established in 1898 on land granted by King Rama V, under two conditions: it could never be sold, and only foreign nationals could be buried there. Over the years, it has become the final resting place for members of various foreign communities, including missionaries, teak company employees, diplomats, and ordinary expatriates—mostly British and American. The cemetery is managed by a committee linked to the British consulate, with no official religious affiliation, though most of those buried there were Protestant.

Our first stop is the Foreign Cemetery. It may seem unusual to begin at a cemetery, but here, honoring ancestors is a natural gesture. We visit the graves of Daniel and Sophia McGilvary, the first Christian missionaries to reach Chiang Mai in 1867, founders of First Church, and pioneers of girls’ education. Alma leads a Christian prayer, and I notice the participants’ gazes wandering over the tombstones. They read the engraved names, recognizing those who founded schools, hospitals, and companies that are still part of daily life in Chiang Mai today.

We cross the Ping River on a pedestrian bridge. In the neighboring district, where houses are very modest, the walls still bear the harsh marks of the last flood. The residents greet us, curious to see our diverse group wandering through their narrow streets.

We arrive at Al Jamiah Mosque, where Ajarn Jirachai, accompanied by a young Malaysian, welcomes us warmly. We step inside for a Muslim prayer. Then, Ajarn Jirachai invites us to make a short detour to his home. We would be tempted to stay—the steaming samovar is enticing—but we are expected at St. Vladimir Orthodox Church.

Father Pavel has just finished celebrating the Orthodox Christmas Mass. After introducing his work, he offers an Orthodox prayer for us. Ajarn Jirachai meets Father Pavel for the first time and gifts him a scarf from India—a beautiful moment of spontaneous sharing and friendship.

We reach Sacred Heart Cathedral just before noon, where the Focolare group leads us in a Catholic prayer. The cathedral’s parish, Father Chanchai, would have liked to welcome us, but a meeting prevented him from doing so. A few days earlier, he had expressed his joy at our interfaith pilgrimage initiative.

We then share a vegetarian Thai picnic in the garden.

In the afternoon, we continue our journey to Wat Chaimonkon, a peaceful riverside temple. There, a Buddhist monkwelcomes us, recites a blessing prayer, and ties a sacred cotton thread around our wrists—a symbol of protection and goodwill. This temple is known for the practice of fang sang (ปล่อยสัตว์), the release of animals to accumulate merit, though we did not take part in it.

Why is the statue of Rama V in this temple important to us?

King Rama V is a respected figure for his modernizing reforms. He opened the country to other religions and laid the foundations of a modern multicultural society at the turn of the 20th century.

We pass by the Library of the Alliance Française d’Exrême Orient, a place that houses the complete literary archives of the region’s history.

Then, we arrive at Shiraz Jewelry, owned by the pioneering Bahá’í couple of Chiang Mai. Maliheh and Nasser settled here over fifty years ago to support the city’s emerging Bahá’í community. Lea welcomes us with music, her guitar accompanying the words of Blessed is the spot and the house and the place… Then, in a beautiful spirit of unity in diversity, prayers are recited in English, Persian, and Thai. On the table, fresh fruits await us—a welcome offering in the heat of the afternoon.

We walk through Kad Luang, the grand market, then cross the historic Khua Khaek pedestrian bridge. We arrive late at the Sikh Gurudwara, but Frank welcomes us warmly, leads us to the top floor, and offers us a blessing in the Sikh tradition. Unexpectedly, he also asks us to pray for him. « I have prayed for you; please, I would like someone to pray for me. » A beautiful example of reciprocity.

A red taxi (songthaew) takes us back to the Gymkhana Club. It has been a day full of meaningful encounters—thank you all for taking part. I hope we will organize this pilgrimage again; I already have an idea for a new route. Now that we have more experience, we might even welcome a larger group next time.

We crossed two pedestrian bridges over the Ping River.

The Chansom Memorial Bridge, also known as Khua Khaek, connects the Wat Ket neighborhood to the Warorot Market (Kad Luang). Its history dates back to 1878 when an American missionary, Dr. Marion A. Cheek, built a teakwood bridge. Destroyed by a flood in 1932, it was temporarily replaced by a bamboo bridge.

In 1965, Motiram Korana, an Indian textile merchant, funded the construction of a concrete bridge in memory of his wife, Mrs. Chansom. Inaugurated in 1966, Khua Khaek (« Bridge of the Indian Foreigners ») stands as a reminder of the Sikh community’s presence in the neighborhood. Damaged by floods in 2011, it was renovated and reopened in 2016.

Why compare this walk to other pilgrimages?

All around the world, believers embark on spiritual journeys: the Camino de Santiago, the Hajj, the Kumbh Mela, Buddhist pilgrimages… Each tradition has its own sacred paths. On a local scale, we created our own route of peace and dialogue. However, our pilgrimage had no ultimate destination—the true meaning lay in the journey we shared.

What is the significance of this pilgrimage in Thailand?

Here, it is common to visit nine temples in a single day to gain merit, a practice known as « ไหว้พระ 9 วัด » (Wai Phra Kao Wat). This tradition honors the Buddha in multiple places and aims to ทำบุญ (tamboon), the accumulation of merit. Our approach was same same but different: by connecting various places of faith, we were not seeking blessings as much as celebrating diversity and weaving bonds of unity across spiritual traditions.

Hans, one of the participants, created a video after the pilgrimage, using footage from the day to highlight the impact of connecting neighboring communities and fostering mutual understanding. It explores the history of interfaith interactions, challenges of prejudice, and the role of such experiences in peacebuilding.

Watch it here: https://youtu.be/IHvUwAZDkbw?si=cg2PESq-u2lLeF6E

text : Frédéric Alix, photos : Hans Hansen + Frédéric Alix ©2025

Laisser un commentaire