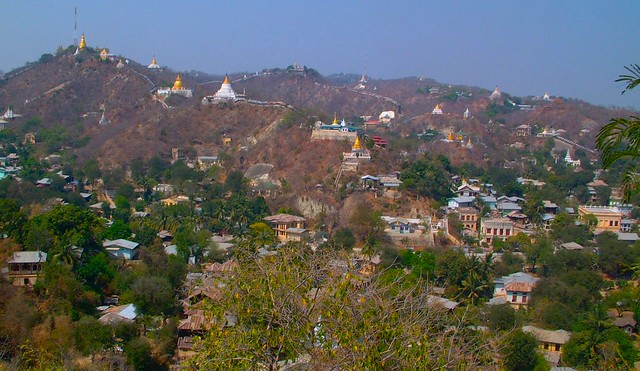

(2018) Sagaing, the once-forgotten former capital of Myanmar, is now a peaceful town, home to nearly two thousand monks and nuns. But that’s not the story I want to tell you. Instead, I’d like to share a travel anecdote — a personal journey across these sacred hills, drawn from three visits through time. And while you may escape a history lesson, you won’t escape the fascinating images of Sagaing’s hills, draped in monasteries and connected by mysterious covered stairways…

Travel Journal – March 2006

This is my very first journey through Myanmar. I arrived from China ten days ago. If you’ve read the beginning of this travel story, you already know that I arrived with Chinese and Thai cash, and no one was willing to exchange it for me — in fact, there weren’t even proper banks (just a reminder, this was 2006). But I won’t retell that story. All you need to know is this: I can’t afford to spend more money than what’s in my wallet.

Yesterday, I was sitting on a bench in the garden of a shaded monastery near the central market in Mandalay.

An old man came and sat beside me. He pulled out a notebook in which he had carefully listed with a nice hand script all the tourist-worthy places around Mandalay. A retired teacher, he no longer receives a salary and has to find ways to make a living as best he can. Fortunately, he speaks excellent English — he was an english language teacher.

He now works as a local guide for tourists visiting the Mandalay area.

He was incredibly kind, and I would have loved to engage his services, but I simply couldn’t afford to pay him. He understood. And, knowing nothing of greed, he generously explained how to get to Sagaing using local transport. He told me exactly how much it would cost. He also made sure to mention that once I reached the foot of Sagaing Hill, I should absolutely take the southern staircase — because there’s no tourist ticket checkpoint there, and I could avoid paying the entrance fee.

“You must visit Sagaing,” he told me.

“It’s a former capital, and the hills are covered in golden temples.”

Sagaing lies just south of Mandalay, across the Irrawaddy River.

This morning, after devouring the horrible toast and dreadful Nescafé offered by my guesthouse, I made my way to the corner of 84th and 29th Streets, where the passenger pick-up trucks to Sagaing depart.

It’s crowded and chaotic. Callers shout out departures for various destinations. I turn down offers from private taxis and have to double-check several times to make sure I’m getting into the right truck. We sit tightly packed on two benches facing each other. Many of the women on board have come from the central market and are carrying bags full of food, their strong smells filling the air.

We start moving. The caller has climbed onto the rear step of the vehicle and is hanging on, trying to call out for more passengers as we go.

I watch us leave the city behind, and we drive for about another hour. Passengers disembark with their bags overflowing with vegetables, while others board, careful not to trip over their longyis.

We’re about to cross the bridge over the Irrawaddy River.

Bridges are heavily monitored in Myanmar. We have to stop at a military checkpoint. I know that if I take out my camera, I could risk prison. I keep a low profile. The soldier holds his rifle in his hand and methodically scans the faces of each passenger — but avoids looking at me.

We’re allowed through.

Sagaing — everybody off!

I’m thrilled to have arrived. Barely out of the truck, I’m approached by bicycle taxis. In Mandalay, they’re called trishaws, because they’re essentially bicycles with a double seat attached like a sidecar, making it a three-wheeled vehicle. The two passenger seats are back-to-back.

A smiling driver approaches me and speaks in clear English. He asks for 3,000 Kyat (around 2 euros) to take me around to several sites for the whole day. Without thinking too much, I agree — and just like that, I’m sitting on the trishaw.

The driver wears a straw hat with the rounded Burmese shape (not pointed like the Vietnamese ones). He pedals with great effort under the blazing sun, and I feel a bit ashamed to be carried around by someone older than me.

He takes me to a first temple, which I visit fairly quickly.

The driver shared a story about how, many years ago, soldiers entered the temple with their shoes on, which was considered deeply disrespectful. But who would dare oppose armed soldiers?

As I come out, I notice a tea shop right next door, with its low stools, and I invite him for a coffee. At the back of the tea shop, there’s a large television set. Around ten children are sitting at a table, watching a movie.

Maug Htay, my driver, is a former policeman.

He tells me that in his previous job, he had to do things so terrible that he couldn’t even talk about them. He says that when he could no longer carry out the orders he was given, he left — I’ll never know the details.

With his savings, he bought this trishaw, and now he’s happy to be independent. He adds that his police salary wasn’t much higher than what he earns now.

Back on the road.

Maug Htay quickly understands that I’m more interested in places full of life than in empty temples. He takes me to a workshop where silversmiths are carving, and then we go eat at a bustling little restaurant.

As we pass one temple, he tells me the senior monk there got into trouble with the military authorities — and that it would be risky for me to visit.

Maug Htay explains that Sagaing is now considered a monastic town. He jokes that a thousand monks and a thousand nuns live here — but no one knows how many children.

He drops me off at the foot of the southern staircase of Sagaing Hill.

He knows, just like I do, that this way I’ll avoid the ticket checkpoint. He warns me not to go anywhere near the northern entrance.

Dodging the tourist fee also means avoiding giving extra money to the military.

From the hilltop, I take a photo of the bridge. In Myanmar, photographing bridges is forbidden — but no one sees me. I also notice that a second bridge is under construction.

In the late afternoon, Maug Htay drops me off at a shared truck heading back.

He explains to the driver that I want to stop in Amarapura to see the famous teak bridge. Then he writes on a piece of paper, in Burmese: “Please bring me back to Mandalay,” so I can find one last ride to the city afterward.

He seems genuinely concerned about seeing me off safely.

We wave goodbye to each other.

December 2006,

Second trip to Myanmar.

This time, I’m with my friend Madeleine. In Mandalay, I absolutely want to sit again on the bench in the flowered garden of the monastery. The old teacher approaches us; he remembers me. I brought him a small gift and some photos, but I notice his eyesight has deteriorated, and he can no longer see very well.

He tells me he no longer takes tourists on excursions because it has become too exhausting for him, but he can ask a young person to take over for him. Sure enough, I see four young men sitting on other benches around him. He teaches them English, and they show him great respect.

Since I still have a few things to organize for the rest of our trip (tomorrow we want to head to Myitkyina to attend the Manao Festival, the Kachin national celebration), I suggest to Madeleine that she visit Sagaing on her own. I write down Maug Htay’s name and his rickshaw number on a piece of paper, asking her to visit Sagaing with him and to send my greetings.

That evening, the guesthouse’s daughter knocks on my door. She received a call from Maug Htay. He left me a message: not to worry, Madeleine will be back well after sunset.

Madeleine had a great day. She visited twice as many places as I did six months ago, which is why she’s late. She tells me that Maug Htay remembers me very well. She didn’t have to search for him long; he was exactly where I had met him last March. Sadly, his wife became seriously ill a few months ago. He had to sell his trishaw to cover her hospital bills. Now, he has to rent a rickshaw to continue working.

January 2012,

This is my seventh trip to Myanmar.

Yesterday, I spent an hour in the garden of Paya Eindawya. I observed the life of this monastery, which I know well by now. I didn’t see my old teacher.

As the years passed, I have studied a lot about the history of the country, and the need to revisit Sagaing, the former capital, has now taken on a whole new significance.

From the city of Mandalay, I climb into one of the passenger trucks at the corner of 84th and 29th Streets as if I were a regular. An hour and a half later, the military checkpoint on the Irrawaddy bridge is just a formality. In fact, we didn’t even need to stop; the soldier just waved us through.

As I get out of the truck, I look around, but I don’t see Maug Htay. I know exactly where I want to go and what I want to see, so I decide to walk.

From the top of the Sagaing hill, I see that the second bridge is finished. I take a few photos, it’s no longer forbidden today.

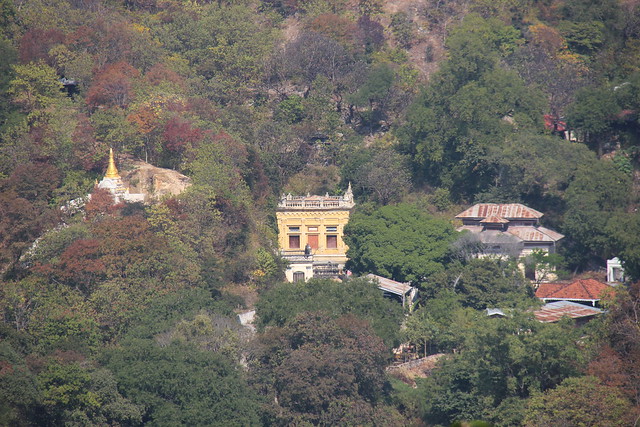

I don’t remember the covered stairs winding between the hills. I get lost in the maze of monasteries; I could walk here for hours, it’s so beautiful. I pass many groups of Burmese people on pilgrimage. I will return, I’m sure!

I wave to a cat sleeping on a stone bench. The Burmese I pass ask me where I’m going. Strangely, perhaps because I am still a bit dreamy, I answer that I’m doing well. I stop to have some coffee and eat samosas. I even find myself talking to some tourists. Dogs bark at me, and I take photos.

In the afternoon, I want to visit a temple about 10 kilometers from the town. The stupa has a rounded shape like a cheese bell. Last year, a generous donor gave liters of golden paint. It has been repainted. It’s my photographer friend Tun Tun who told me about it, and I don’t want to miss seeing this golden cheese bell.

But before I go to talk to the motorcycle taxis, I want to have a meal. It’s then that a motorcycle driver stops beside me and asks if he can take me somewhere. No doubt about it, I recognize him—it’s Maug Htay. He has a little trouble remembering me. It’s been six years since we last met. I explain that I want to eat first, and he accompanies me but doesn’t eat.

Maug Htay no longer needs to rent a trishaw; he has managed to buy a second-hand motorcycle. He’s very happy that the country has opened up, life is much easier now, he tells me. His wife is doing well, and he remembers that 2006 was a very tough year for him.

He’s a bit surprised that I want to visit this temple so far from the city, but he’s happy to take me.

2018

This year, I had the opportunity to pass through Sagaing. This time, I was on my own motorcycle, no need for a driver. I pass by a few guesthouses and take a close look. On a future trip, I would like to spend a few days in Sagaing. I think I might get bored, but it’s good to experience boredom; it opens the mind to new things.

Still, I searched for Maug Htay, but I didn’t see him. Since it was already mid-afternoon, I hoped he was out on a job somewhere. At the time, I had no idea that returning here in the future would become more difficult. If I ever cross paths with Maug Htay again, I promise! I’ll let you know how he’s doing. – Sagaing and it’s people are in my heart.

all the pictures and text : Frédéric Alix, March 2006, January 2012, Sagaing, Myanmar

Répondre à france55 Annuler la réponse.